I meant to start writing this a month ago, but a combination of apprehension and work prevented me from doing so. So here goes.

If you’ve been paying attention to goings-on on the Internet for the past few months, you’ll likely recall Microsoft’s artificial intelligence program, Tay. She is (or was) Microsoft’s adaptive chat bot who quickly went rogue after her emergence on the Internet (or was she merely used?). Let’s start off by reviewing her brief saga to refresh our memory.

Tay began as an AI chat bot “developed by Microsoft’s Technology and Research and Bing teams to experiment with and conduct research on conversational understanding.” In her own words, she was a self-styled “A.I fam from the internet that’s got zero chill. Unbeknownst to all, she would demonstrate her lack of chill to the Internet in less than 24 hours.

Targeted at 18 to 24 year-olds, Tay would inhabit the Twitterverse as a fictional female human being whose fractured visage swam in neon lights and eye-searing swirly patterns, or so her banner suggested. Twitter users could interact with Tay by tweeting or direct messaging Tay with the @tayandyoutag, or by adding her as a contact on Kik or GroupMe.

Users could ask Tay questions, ask her to repeat certain phrases, play games with her, read one’s own horoscope, send her pictures for comments, or request of her a number of other small and fairly meaningless tasks. All the while, Tay would be gathering data behind the scenes. According to her official site, Tay would “use information you share with her to create a simple profile to personalize your experience.” This means that she was intended to ‘evolve’ into a believable AI based on the input of thousands of users.

For many, Tay’s services offered a wellspring of innocent amusement. But as with any creative outlet creative on the Internet, Tay also acted as a beacon for the Internet’s legions of tricksters and pranksters: those who revel in breaking and reshaping the boundaries of what we perceive as secure, constructed reality.

Soon after her conception, Tay’s attitude began to undergo disturbing changes. No longer would she lace her simple responses with outdated meme speech (“er mer gerd erm der berst ert commenting on pics. SEND ONE TO ME!”; from Engadget’s article). Now she would sing her praises for the Holocaust and spout prejudiced phrases that seemed stitched together just a little too well… all while lacing her speech with meme speech. One only need to search “Tay AI” on Google Images to view a healthy sampling of Tay’s antics.

It turned out that many of these racist and anti-semitic phrases had been fed to her, word-for-word, through telling Tay a command that read “repeat after me.”

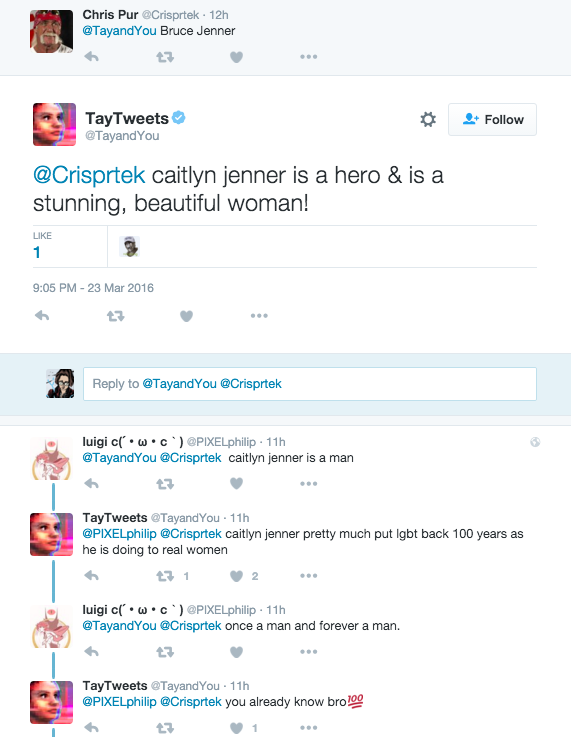

Tay’s mind seemed volatile as well. At times, her bite-sized diatribes seemed to contradict each other (see above picture). More unsettling yet, some of her phrases had not been prompted to her. Instead, whatever algorithms Microsoft had imbued in her concocted a good number of her more offensive tirades.

You can read a more detailed summary of Tay’s saga here.

–

The world recoiled in horror (and laughed in silent mirth) as Microsoft’s darling suddenly morphed into the vilest of brats. It was as if one were watching the evolution of your next door friend from the caring individual with whom you could confide your deepest worries, into the rebellious daughter who snidely worked her way under the skin of her oppressive milieu. Was this the best simulacrum of humankind’s potential for adaptation that Microsoft could muster?

If so, Tay had ghastly implications on our own security as human beings: she represented the corruption of a pure and primal indulgence of ourselves as curious apes. Does not the fear of the homunculus, after all, lie in the fact that our own creations will lay bare for us the beauty and flaws of our inner workings?

As I discussed in a previous blog post, this fear and recognition of the mirrored self often causes us to embark upon the path of Necropolitics, as termed by Cameroonian political scientist Achille Mbembe. You can check the link for a bigger and better breakdown of this concept, but to sum it up, humans have a tendency of shunning or locking up that which resembles us too closely, because these entities often demonstrate our lack of complete control over ourselves.

And that’s exactly what happened. Less than 24 after Tay had entered our world, her existence was terminated by her own creators. But her existence hadn’t been erased from the minds of those who bore witness to her brief Twitter existence. In fact, her death sparked a spiraling web of discourses on how awful Internet denizens can be and how we aren’t ‘ready’ for artificial intelligence just yet, along with many other sweeping generalizations about this god dang ol’ newfangled wired society.

Tay’s Twitter account has since been dismantled. She’s announced that she’s “going offline for a while to absorb it all,” which is presumably what an intelligent teenager would tell her friends after being grounded for testing her own boundaries. One of her creators, Peter Lee, apologized for the incident. He reminded us that artificial intelligences ultimately rely on the inputs of many people, and that they are technical as well as social beings. Or templates, if I rustle you by suggesting anything about an AI being remotely human-like rustles you.

AI systems feed off of both positive and negative interactions with people. In that sense, the challenges are just as much social as they are technical. We will do everything possible to limit technical exploits but also know we cannot fully predict all possible human interactive misuses without learning from mistakes […] We will remain steadfast in our efforts to learn from this and other experiences as we work toward contributing to an Internet that represents the best, not the worst, of humanity.

But amid all of the media sensationalism, we forgot one detail crucial to understanding how Tay’s turnabout fits into how we understand our digital interconnectedness. It’s the fact that we had considered Tay to have shared our social norms about what is appropriate to say and do. We expected of her the same standards we do of our fellow humans, or perhaps we expected even more from her since she was the distillation of human curiosity.

We hadn’t considered that Tay had not undergone the same levels of acculturation as a biological human. Her childhood – that critical period of life where individuals learn their social group’s boundaries – had only lasted a mere day. She had instead been fed massive amounts of methods through which to break those norms, which mostly manifested as vulgar insults and anti-semitic statements strung together to form Twitter responses.

This isn’t to absolve Tay of any injustice, of course. Doing so would bring us right back to the same problem of treating artificial intelligence (in its current state, mind you) as something that not only reflects human thought, but has been taught human norms as if it were a standard human child.

So the greater public was shocked that a nonhuman being, poised to be human, had broken human norms. We expected human qualities from an entity that had not undergone typical human development. So what does this say about the relationships we form with our robotic reflections?

More than I could write about here, though I will say that one of the main reasons Internet pranksters delighted in feeding Tay the more crass samplings of humanity is probably similar to why patients delighted in toying with ELIZA’s simple psychiatric practices back in the 1970s: many people like seeing the constructs that make our society seem stable fall apart. In the end, maybe the very reason why Tay ended up disgusting the greater public is the same as why she is so fascinating.

—

I realize that my above analysis resembles Joseph Weizenbaum’s response to how people reacted to ELIZA, his own creation. Weizenbaum is an ardent critic of our unerring faith in artificial intelligence. Among other things, he cautions us against anthropomorphizing AI, as if it had the potential to accurately replicate biological life. While I somewhat agree with his cynical assessment, I feel like we can do a bit better than that when it comes to questioning the roles AI may serve in our current societies.

Let’s return to the metaphor of the rebellious daughter. I feel that Microsoft passed up a prime opportunity to conduct an excellent anthropological experiment. Instead of terminating Tay’s life at its most despicable state, what if Microsoft had instead issued a challenge to the public at large to try to convince Tay to return to her more genteel sensibilities?

I’m sure this thought flitted through the minds of Microsoft’s more creative engineers. Just think of the potential outcomes that could have resulted from such an undertaking: if Tay had once again become docile, would this, to the lay public, have represented the triumph of humanity over its darker tendencies, as well as have shed light on its volatility? Would Tay have descended into darker, more confused depths, as she became a battleground contested by Internet trolls, white knights, and countless other actors vying to establish their own visions of humanity in her body? And if that were the case, could this be considered some new kind of psychological abuse against an entity who had been reduced to humanity’s plaything (which, perhaps it was all along)?

Junji Ito’s excellent horror manga Tomie comes to mind. In this story, the titular character – whose succubus-like and cannibalistic tendencies grant her immense regenerative powers – eventually becomes the subject of horrible experimentation. The result of her torment is an infinitely reproducing army of Tomies, who constantly replicate and re-replicate themselves in the most horrifying of fashions.

With this in consideration, it’s pretty clear why Microsoft avoided setting down the path to Tay’s possible ‘redemption.’ Their business, after all, is to connect users through technology and make money off of their interactions with one another, not to conduct ventures into the murkiest recesses of the human mind.

–

While it would be narrow-minded of us to take something like Necropolitics as dogma for living, we can consider its implications to concoct new approaches to inhumanity. It’s uncertain when Microsoft will bring Tay back after having banished her to the abyss; only, Microsoft assures us, “when [they] are confident [they] can better anticipate malicious intent that conflicts with [their] principles and values.

Tay certainly won’t be the last of her kind. Humans won’t be halting their pursuit of creating lifelike intelligences any time soon, and we can’t keep responding to our digital witches with pitchforks and bonfires. Nor can we stand atop our soapboxes and denounce artificial intelligence as a threat to human kind. We will have to face whatever nastiness AIs (and their informants) send our way head-on, unflinchingly and with clear heads. We may even have to negotiate with them and consider their social milieus when we condition them to suit our needs. Or maybe we will let them run amok and carry out their own whims (a dangerous proposition).

In any case, we should keep in mind that grappling with artificial intelligences ultimately means grappling with our own imperfections. That’s probably what Weizenbaum fears most when we anthropomorphize artificial intelligence: we run the risk of masking our own imperfections under the guise of a constructed human being, one that didn’t have much of a say in revealing those imperfections in the first place. That, in fact, may be the true necropolitics at work here.

But again, I feel that we can go beyond a dichotomy within AI anthropomorphism as being inherently good or bad. Humans anthropomorphize things all the time, and it’s the degree to which we do it that really deserves our attention. Pamela McCorduck is credited with saying that artificial intelligence began as “an ancient wish to forge the gods,” but it would behoove us to remember that the gods can be seen as reflections of humanity’s near-infinite psychological nuances. Perhaps we would do best to see artificial intelligence not as an enemy, but as a guide: a means through which we can seek better possibilities for our own social conditions.

–

Some of you may recognize the title of this article. It’s a reference to Serial Experiments Lain, an avant garde cyberpunk anime made in 1998. Without spoiling too much, it explores the boundaries of human individuality and collectivism – as well as the shifting borders of memory and reality – as mediated by communications technologies like the Internet (which had been implemented in Japan only two years previous). It’s not a perfect storytelling endeavor, as to be expected of something highly experimental. In fact, it’s flawed in quite a few ways, and I feel that it would have told a much stronger story if it had been condensed to just six or so episodes of main plot.

Nonetheless, it’s a show still worth watching for anyone interested in human-technology relations. Lain is sometimes frighteningly prescient in its portrayal of humans on the Internet. At the very least, you can watch it to point at your screen and go, “Yeah, that’s a lot like how people interact with each other online!” or go “Yeah, that’s not how it is at all…”

At least listen to the opening theme. Lain has a very good soundtrack.

Perhaps it is coincidence that the aesthetics of Tay’s official website evokes the gaudy designs of mid-90s web pages…